Runners with Knotted Cords - Running Through History

I recently returned from Albuquerque, New Mexico, where I learned a cool story about runners in the American southwest who changed history. I'll relate that in a moment... but it occurred to me just how little I know about running and its role in world events.

If you ask most runners about the role runners have played in history, I'm guessing many would mention the same story: the one about Pheidippides. He's the messenger of ancient Greece who ran the 246 km from Athens to Sparta to request help when the Persians landed at Marathon, then back to Athens to let them know the Spartans were happy to help, but couldn't leave home until after the full moon -- so the Athenians would be on their own for several days, fighting the Persians on their own.

Even though he'd just run almost 500 km, Pheidippides joined other Athenians in marching to Marathon to push off the Persians. They fought, and though the Greeks were outnumbered 4 to 1, after sustaining heavy losses the Persians fled. So Pheidippides -- you guessed it -- ran from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory over the Persians. According to Lucian, after uttering "Joy to you, we've won," he collapsed and died.

As an aside, I find it a disservice to Pheidippides' memory that the "marathon," the race named in memory of Pheidippides' incredible public service and endurance, is only 26.2 miles -- just that final leg from Marathon to Athens -- given that Pheidippides had actually run closer to 360 miles in his final days. But I digress.

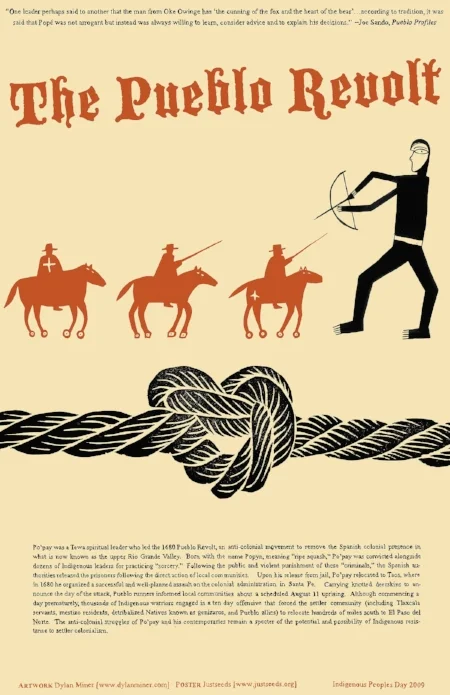

Dylan Miner created this commemorative poster about the Pueblo Revolt in honor of Indigenous People's Day 2009, which you can purchase here if you like.

I write today to share a less-well-known story about runners in the past, one that happened right here in North America. It starts in 1675, when Popé, a religious leader from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo (north of Santa Fe, New Mexico), was arrested along with dozens of other Native people by the Spanish authorities, and convicted of "sorcery" -- basically, for practicing his religion.

Four of the men were sentenced to hang, and the others were all whipped. Infuriated by this injustice, representatives from the various Pueblos descended upon Santa Fe and demanded the release of the captives, threatening war on the Spanish if they were not allowed to go free. Governor Juan Francisco de Treviño, who at the time was also under threat from other Apache and Navajo groups, released the prisoners -- but the repression of Native religion did not end. Under the Spanish repartimento system, Pueblo people were expected to serve as slaves to the Spaniards, supplying them with food and tools. Spanish vandals filled kivas with sand, preventing Pueblo people from engaging in the dances that helped them communicate with the gods.

After his release, Popé moved to Taos Pueblo, and along with other Pueblo leaders, started to plan an uprising. But they had a challenge: how to unite two dozen different communities who spoke six different languages and whose Pueblos spanned more than 400 miles, from Taos Pueblo in what is now north-central New Mexico, to Hopi villages that were in what is now central Arizona? Compounding the problems of language and distance was the fact that under Spanish rule, Pueblo people were forbidden from using horses.

So Popé and his compatriots came up with a simple but effective communication method: they dispatched runners with knotted cords out to all the various communities, instructing that the people were to untie one knot each morning as a countdown to the day of the revolt. The revolt was set for a day in August 1680, numerous cords were knotted accordingly, and runners distributed the cords over the huge territory recruited to join in the revolt.

The countdown didn't go exactly as planned -- the uprising began one day early -- but all the same, the Natives' success was astounding. After 10 days of fighting the Spanish in Santa Fe, the Pueblo people forced the Spanish to flee the city. The Spanish attempted to regain control but were rebuffed in 1681. A 1687 attempt failed too. It took until 1692 for the Spanish to regain control in New Mexico, despite having more advanced weaponry, meaning that Popé and the runners with knotted cords succeeded in gaining 12+ years of independence for their people.

Wishing you years of independence, and the fortitude to communicate with anyone you need to reach, I will see you on the trail!